Last September, I published my book A Swede on the Hippie Trail (1974). Six months later, Rick Steves released On the Hippie Trail: Istanbul to Kathmandu and the Making of a Travel Writer (2025). These are two of the latest in a growing crop of travel books and memoirs from the Hippie Trail, which attracted hundreds of thousands young travelers until it was closed by the Iranian revolution in 1979.Like millions of others (Rick Steves has 1.2 million followers on Facebook) I am a huge fan of his European guidebooks and PBS specials. His books are down-to-earth, and well researched—very useful when planning a trip or finding yourself looking for a way to avoid the long lines to the Louvre or the Uffizi Galleries. He is also a man who doesn’t hesitate to call-out evil when he sees it, whether through a television special on the history of fascism in Europe or calling out Donald Trump as the fascist he is.

Rick’s new book is beautiful and a delightful read. He tells the story of the journey his and his friend Gene Openshaw did along parts of the old Silk Road that in modern times became known as the Hippie Trail. Having been bitten by the “travel bug” backpacking around Europe in 1973, they met up in Frankfurt in July 1978 and set out for Istanbul. Although not hippies, the two 23-year-olds wanted to see India and Nepal, which in those days were popular destinations for hippies and young adventurers.

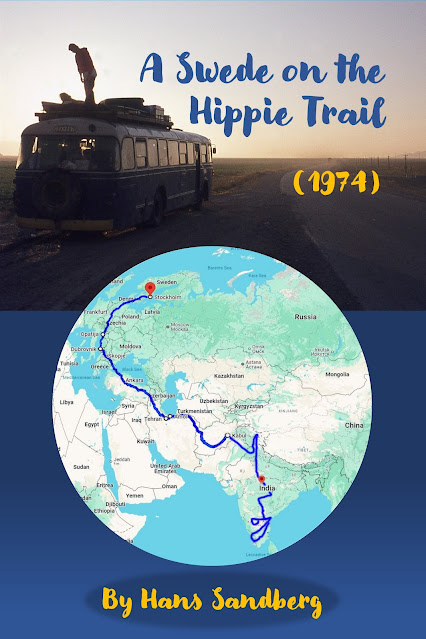

My book starts out four years earlier, in September 1974, when my then-girlfriend Elisabeth and I boarded one of two blue Scania buses set for India. We were 20 and had worked in a slaughterhouse over the summer to make money for the trip. The deal was that the buses would take us to New Delhi, park there for five weeks and then take us back to Sweden. We slept on the buses, which had been refurbished for the purpose. There were a couple of fellow travelers who talked of smoking pot on a rooftop in Nepal, but we were heading for southern India, maybe even Sri Lanka (then called Ceylon).

Our two books have similarities, reflecting the fact that our journeys from Istanbul to Srinagar in Kashmir and New Delhi overlapped, but they are still very different. Rick Steves built his book around his lightly edited 60,000-word journal, plus photos that he and Gene took. His story is charming, naïve and has a strong sense of presence. Unlike me, he was an extrovert who didn’t hesitate to ask a farmer if he could try out his ox-driven thresher or ask a female farm worker to carry her heavy load for a bit. It’s all there in the diary and the photos. We see him engaging with people he meets. He and Gene also took many photos of themselves documenting their 55-day-long journey. There was also something romantic about his approach, which was very different from mine.

“The Khyber Pass! I had dreamed of crossing this romantically wild and historically dangerous cultural divide for years. It was very high on my life's checklist of things to do in the top five for sure. I'd read all about its illustrious history as the gateway to India.” (p 82)

When reading his story and hearing him talk about it at his book launch in New York earlier this month, I got the sense that this was not only a trip in the now, but something that would change his life, which it did, once he had returned home. He became a travel writer.

Being a Swede, I was an introvert at home, but an extrovert on the road. I was an atheist, politically radical, and always on the lookout for inequality and poverty. I too was naïve, but also open-minded. Although we traveled somewhat cocooned in our bus to and from India, we had many opportunities to meet and engage with local people, mostly young men who spoke some English. During our five-week train travel through central and southern India, we had nowhere to “hide,” so we had to engage. Like Rick, I wrote a diary of sorts, but my entries were sporadic and not enough for a book. Hence, I had to build the book on my 100-day-long journey by digging into memories, going over my over 1,300 photos (regretting that I only posed for two!), and doing a lot of research. I read everything I could find, from Hans Christian Andersen, Robert Byron, and William Dalrymple—to Marco Polo, Rory Stewart, and Michael Wood.

The result is two very different stories. The strength of Rick Steves’ book is that he invites you to be with him during his journey, to share his perspective as a 23-year-old kid on the adventure of a lifetime, but his framing sometimes limits his story. When he visits “some old, ruined minarets in the distance” (p 82) in Afghanistan, he is not aware that they were part of the Musalla Complex, one of the great wonders of Timurid architecture, which sadly had been blown up by British colonialists in a reckless attempt to stop the Russian empire from advancing in the “Great Game.” I was aware of that from Jan Myrdal’s Afghanistan books and could now add context by quoting Robert Byron’s 1937 book The Road to Oxiana. In this way I could go beyond the perspective of a 20-year-old while still offering my personal take through diary entries, letters home, and photos.

Finally, my trip didn’t change me, but his did. I came back as radical as when I left, as young and dogmatic, reading Marx and Mao, protesting U.S. and Soviet imperialism. He on the other hand started a business that changed many people’s lives. He was an American and an entrepreneur. I on the other hand, was a young Swedish rebel, dreaming of a revolution that never came.

,_from_Los_Caprichos_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)